Introduction

Computational complexity is the study of how difficult problems are. In the same way that physics is not about building better rockets, but understanding the natural principles behind rocket construction, computational complexity is not about building better algorithms! Rather, it’s studying problems themselves as separate, natural entities. [1] Broadly speaking, we assign problems to classes denoted by inscrutable series of capital letters (P, NP, PSPACE, EXPTIME, BQP) depending on how quickly the problem becomes stupidly difficult to solve as you try more and more complicated versions of it. That difficulty is given in terms of the resources a computer would have to use. There are more complicated resources (like communicating with other computers) but here we’ll just think about time and space.

What is a problem?

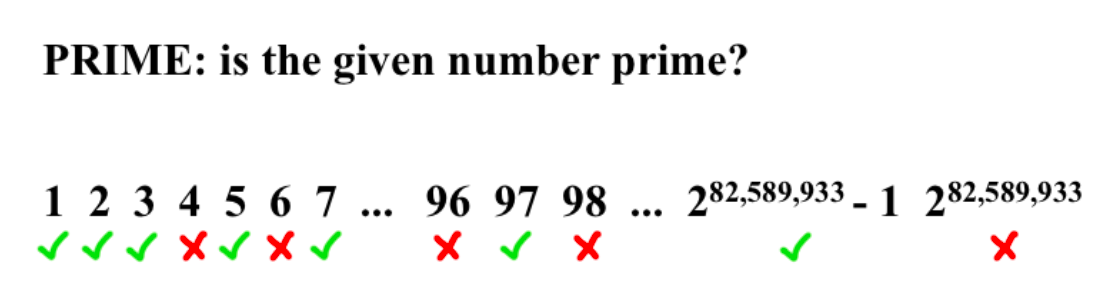

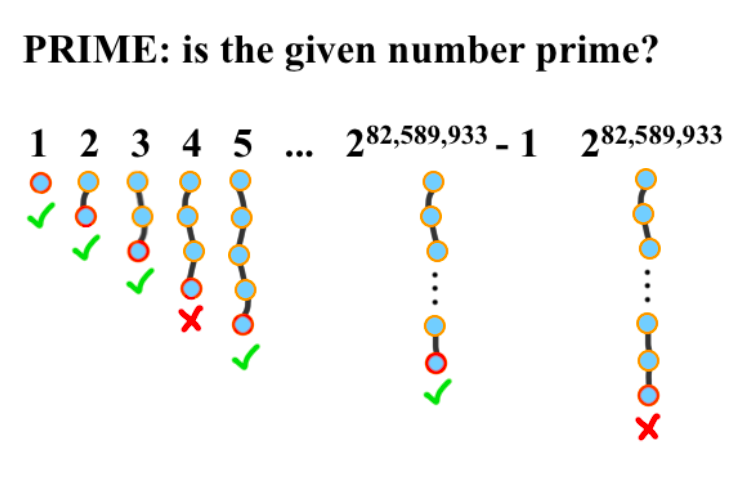

Let’s look at a simple example problem: “Given a number, is that number prime?” This is an interesting problem for a computer to solve because there’s an infinite amount of numbers. “Given a number less than twenty, is that number prime?” is not — the computer could just store a look-up table that tells it whether the number is prime or not, and solve it in no time! A wise man once said that “an algorithm is a finite solution to an infinite problem”.

This problem, which we’ll give the name PRIME, becomes only a little more difficult as each of its values increases. That is, determining whether 1736598123657 is prime is certainly difficult, but it doesn’t take much longer than determining whether 1736598123653 is prime.

Problems like this we call P, which stands for polynomial time — formally, if a problem is in the class P, solving the problem takes polynomially more time as the input increases. Here’s a formal definition:

\[P = \bigcup_k TIME(n^k)\](\(TIME(f(x))\) is just the set of the problems that take \(f(x)\) more time to solve as \(x\) increases.)

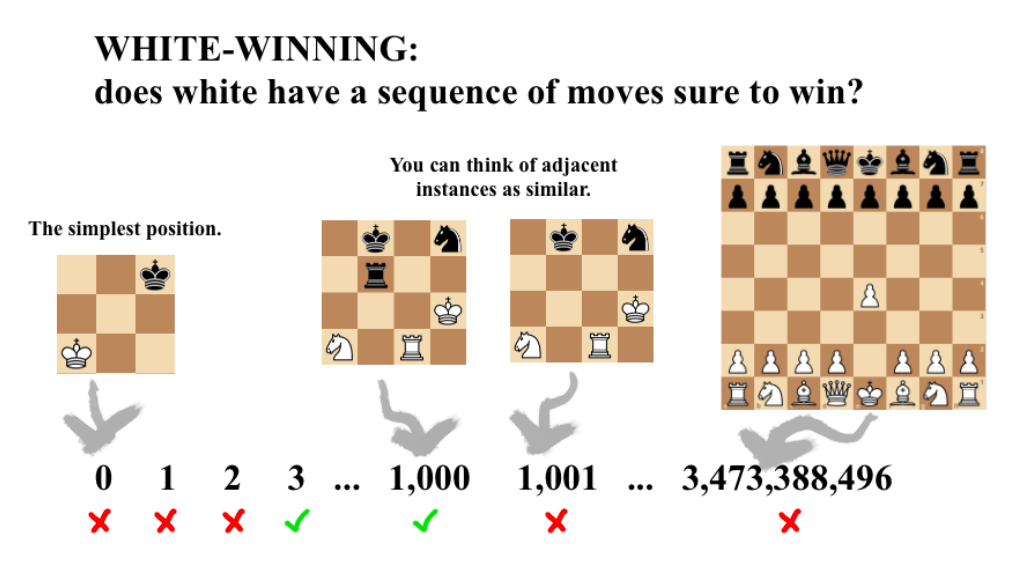

Before we move on to games, there’s some necessary jargon: we say that a problem has an infinite number of instances. In the case of PRIME, each instance is a number. In chess, our problem might be called WHITE-WINNING, which asks “given this initial position, does white have a sure-fire way to win the game?” An instance of WHITE-WINNING would be an arrangement of pieces on the board. So that we have an infinite number of instances, we generalize our chessboard from 8 squares by 8 to any number n squares by n. This allows us to learn more about chess in the 8 by 8 case by learning how much harder chess gets when you make it bigger. WHITE-WINNING is not in P — we’ll see what it is in later on.

Now that you’ve seen some examples, maybe it will be easier to grasp this counterintuitive definition: a problem is any mapping we can make from the natural numbers to a boolean (true or false, yes or no).

KLONDIKE: NP and NP-COMPLETE

For Klondike we examined if the game was solvable from an initial state. If you are not familiar with Klondike, it is also known as “classic solitaire” and it is preinstalled on most Windows versions. Of course, the randomness comes from the deck being shuffled and dealt, and due to the nature of the game not all initial board states are solvable, even with perfect gameplay.

The runtime of contemporary algorithms to find if a game of klondike is solvable is in the class known as NP. In fact, it is NP-complete, which means it is at least as hard as any problem in NP. [further topics: completeness and reduction] It’s the case for NP-complete puzzles that determining whether an instance is solvable is the same as going through the motions and solving it![2] More on this later.

Interestingly, humans are very, very bad at this game when compared to computers. Modern estimates place between 70-80% of initial configurations as being solvable.[3] Human abilities in this game are far lower. There exists a variant of pyramid solitaire known as “Thoughtful Solitaire”. In this variation, the player is able to see all cards which would normally be hidden. In trials with experts, only approximately 36.6% of games were solved, out of a sample size of 2,000. Humans will fail to solve a solvable game about half of the time, this is when they are given access to all cards which would normally be hidden.

A human, even knowing all the cards, cannot plan far enough ahead to properly win the game, so this leads to the greatly decreased rate of successful solutions compared to the rate calculated by contemporary algorithms, which can keep track of all possible “routes” as easily as it can multiply two absurdly large numbers.

But why is Klondike NP-complete, and what is the class NP?

Let’s take another look at the class P. Remember the problem PRIME? Well, one way of drawing the instances is like this:

Where the length of the lines might indicate the length of the computation to figure out whether the number is prime. (One way is to try to divide by every number less than it!)

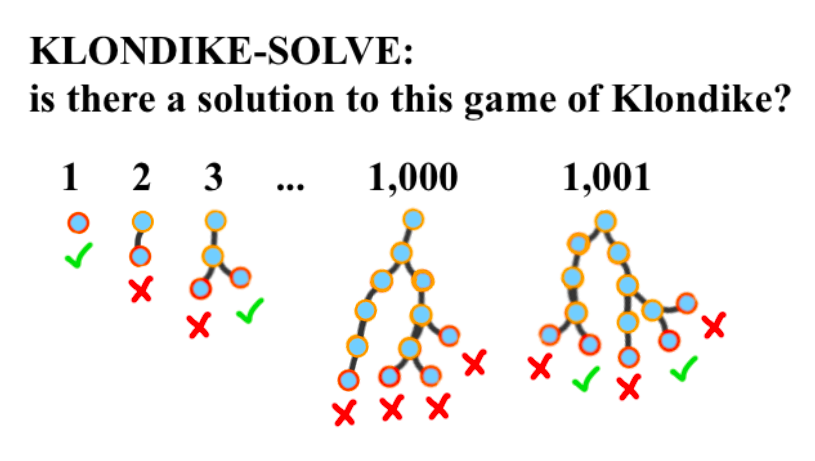

Let’s name the problem of whether or not an initial condition of Klondike is solvable KLONDIKE-SOLVE. That initial condition will be our problem instance. Then, there’s lots of ways to generalize Klondike to have an infinite number of instances — let’s say we keep increasing the number of suits past four, or the number of ranks past 13. (2 through 10, Jack, Queen, King, Ace.) To check whether a game is solvable, we can’t just do something simple like divide by every instance less than it — we have to play through each game! The computational path might look like this. (This is an exercise for you, dear reader: imagine the instances of the solitaire games that are being mapped to each natural number, as the author doesn’t feel like drawing them! What might it look like when the number of cards changes? Make your own solitaire generalization.)

KLONDIKE-SOLVE asks, “does at least one of the ways of playing the game, starting from this instance, end in a solved game?” For instance #1437, this is true — for #1438, there is no way to play the game or make choices such that you win. (Them’s the breaks!)

Now we can look at the formal definition of NP:

\[NP = \bigcup_k NTIME(n^k)\]Remember \(TIME(f(x))\)? Well, that’s all of the problems whose problems get \(f(x)\) harder for a deterministic computer to do as \(x\) increases. You can think of a deterministic computer as a computer that can only follow one path — just like the computer that you’re reading this on. \(NTIME(f(x))\) is a class for computers with the godlike power to go down multiple paths at once, and then select the one it wants at the end! Although these computers don’t exist (and this is not what a quantum computer is — that’s a whole ‘nother deal) we find it useful to study the problems that they might be able to solve.

Anyway, this means that NP is the class of all problems that our godlike computer could solve in polynomial time, as it can “split”. Our regular, deterministic computers can’t split, and so problems that are in NP that aren’t also in P take more than polynomial time.

This should provide some intuition why almost all puzzles are NP-complete — NP are things that are easy (polynomial time) to check the answer to, but hard (exponential time, as you have to check every path) to find the answer to, and that’s pretty much what a puzzle is, right?

CHESS: PSPACE

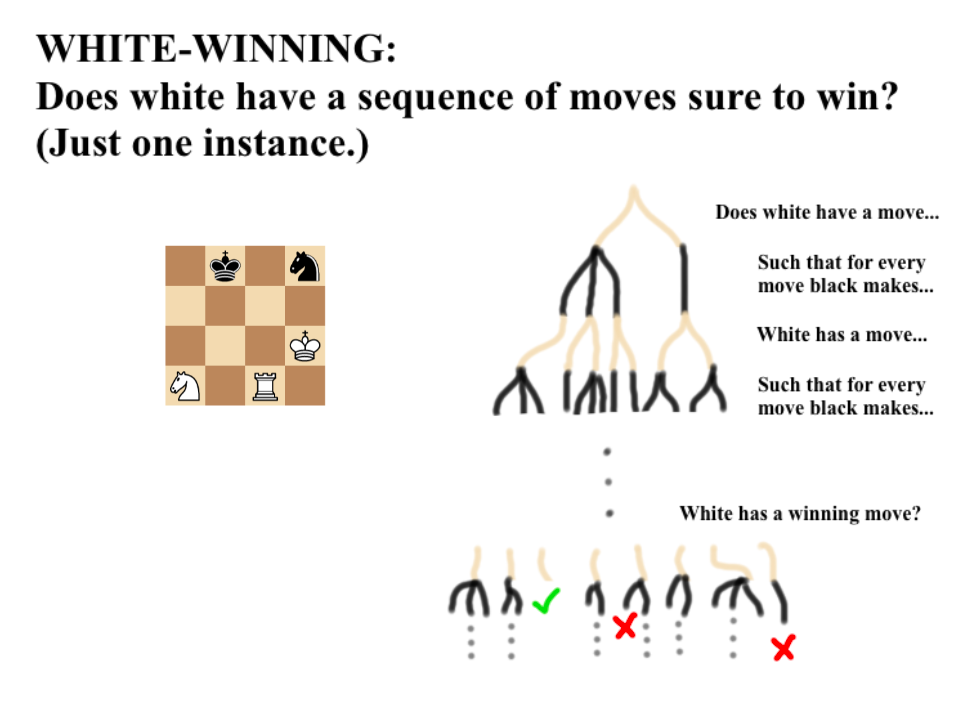

Now for chess. Let’s go back to the beginning, when we were introducing problems: our problem is named WHITE-WINNING, which says, “given this position, does white have a winning move”? As with the previous games, we generalize to an infinite amount of games so we can’t just use a big lookup table. We do this by allowing our chessboard to be any size n x n!

The puzzle we considered earlier, Klondike, was NP-complete, because puzzles take the form “make a move that solves this puzzle”. (Remember? Easy (polynomial time) to check a solution, hard (exponential time) to solve one.) In chess, it’s not just you anymore — you’re playing against an adversary! Chess is “PSPACE-complete”, because the hardest problems in PSPACE are problems that take the form “make a move such that for every move your opponent makes, you can make a move such that every move your opponent makes…” It’s going to take exponential time to go down every one of those paths, but it will only take polynomial space to keep track of where you are in the path. [4]

For completeness’s sake, here’s the formal definition of PSPACE. The details aren’t super important — see if you can suss out the finer points from the definitions of P and NP above.

\[PSPACE = \bigcup_k SPACE(n^k)\]Now, let’s look at WHITE-WINNING with fresh eyes, and draw it in the same “computational path” way that we drew KLONDIKE-SOLVE (although in a simplified manner to save space). For simplicity’s sake, we’ll just look at one instance.

You can see two things when the computational paths of WHITE-WINNING are drawn — first, you can see the “for every move my opponent makes, do I have a move…” recursive structure. Second, you can see that checking a solution indeed takes polynomial time — you simply follow the path back up!

However, this simplicity of checking assumes a rule in chess called the “fifty-move drawing rule”. WHITE-WINNING is in PSPACE if there’s a bottom to these paths [5], but if states are allowed to loop back on themselves, things can go on indefinitely, and we have to keep track of all the past states of the path! [6] Now WHITE-WINNING still takes exponential time, but now it will take more than polynomial space to keep track of where we are. WHITE-WINNING without this drawing rule is EXPTIME-complete, which is a class we will meet while investigating checkers. (Though you might be able to guess what the class means.)

CHECKERS: EXPTIME

Let’s take a look at checkers. We will examine the 8 x 8 version of English draughts with forced capture. There are many differences between klondike and checkers, but our main goal here is to introduce EXPTIME.

Here’s the main question when it comes to checkers: which player will win? Clearly the better player will be favored, but when both players play perfectly the game is proven to be a draw. This makes checkers a “solved game” (see Further Reading for more about solved games).

First, let’s examine how hard it is to solve a game of checkers. How do we tell if a move is the correct move? Unfortunately, there’s no fast way to do this. A computer would have to check many possibilities for future moves and examine countless numbers of game states to see if the move is correct. This algorithm is bounded by EXPTIME, meaning that it would take a constant to the power of a polynomial to compute the 100% correct answer.

Here’s the formal definition of EXPTIME.

\[EXPTIME = \bigcup_k TIME(2^{n^k})\]This means that it takes a normal, deterministic computer exponential time to solve this problem.

Here’s a simple proof that checkers is at most EXPTIME, given an general N by N board:

Each position has 5 possibilities:

- Empty

- White

- White King

- Black

- Black King

There are N^2 locations on an N by N board.

Thus, the total number of possibilities is \(O(5^{N^2})\). (Note that this is a very loose upper bound.) Thus, checkers is in EXPTIME, as many of these positions could be reached in at least one way by normal play, and an algorithm has to go down every one! [further topics: machine learning of games vs. “solving” of games]

Before getting to relating EXPTIME to PSPACE and NP, let’s talk numbers.

A normal board is \(8 \cdot 8\), so let’s see what \(5^{8^2}\) is: \(5 \cdot 10^{44}\).

That is much larger than the number of grains of sand on the Earth: around \(8 \cdot 10^{18}\). [7]

More careful analysis reveals that the number of possibilities for checkers game states is actually less than \(5 \cdot 10 ^{20}\) [8], but this is still comparable to the number of grains of sand on the Earth.

How much would it cost to store the best move for \(5 \cdot 10^{20}\) game states?

Suppose \(5 \cdot 10^{20}\) states can be compressed to 100 positions per byte (this is actually very hard to encode), then you would need 1,000 petabytes of storage:

- 15 GB = \(\frac{15}{1000}\) terabytes: The amount of storage Google gives you for free

- 1 terabyte = \(\frac{1}{1000}\) petabytes: Your computer might have this much storage on a single hard drive

- 1 Petabyte: Usually made with 100, 10 TB server hard drives (around $30,000). A small-medium sized media company might have a few petabytes of storage to store uncompressed video files.

- 1000 Petabytes: $50 million storage solution for a supercomputer [9]

You might wonder how EXPTIME relates to NP. In the case of NP, given a solution, you can check to see if you win in a reasonable amount of time. In Klondike, a victory is a victory. As you are not playing against an opponent, you only need to consider if a move will directly lead to a victory. This is not the case in checkers because you need to ensure that a given move can’t possibly result in a loss. Given a sequence of moves, how do we tell that that sequence is optimal? When it comes to “solving” checkers, a one-move victory is not what we ‘re looking for — we need to find a sequence of moves that makes it impossible for an opponent to win, no matter how well the opponent plays.

However, if checkers has a drawing rule, it is also in PSPACE. This is possible, as PSPACE is within EXPTIME. (In plain English: any computation that can be done in polynomial space can be done in exponential time.) In fact, both checkers and chess with drawing rules are in PSPACE, and without drawing rules are in EXPTIME! [further topics: more games that fit this pattern on the wikipedia page.] But exactly why is beyond the scope of this guide. I think we’ve brought you far enough, and it’s time to summarize what we’ve done here and shepherd you out into the larger world of computational complexity.

CONCLUSION, FURTHER TOPICS, RESOURCES

Let’s summarize what we’ve done:

- We introduced decision problems as, rather unintuitively, mappings from problem instances to natural numbers to booleans.

- “An algorithm is a finite solution to an infinite problem” — in order to talk about games in terms of computational complexity, we have to find generalizations of games that get more complex. (E.g., chess played on an n x n board.)

- We showed why klondike, a one-player puzzle, was NP-complete and why most puzzles will also fall into this complexity class.

- We saw the discrepancy between a human and a contemporary algorithm in their ability to solve klondike.

- Moving on to games, we showed how the presence of an adversary moves the typical game into a higher complexity class than the typical puzzle.

- Where puzzles are often NP, games are often PSPACE and EXPTIME.

- With our analysis of chess, we saw how with a drawing rule complexity was limited to PSPACE, whereas without it, the problem WHITE-WINNING (Given this board position, does white have a winning sequence of moves?) is EXPTIME-complete.

- Checkers, which typically has no drawing rules, has the same level of computational complexity as chess does without drawing rules. (That is, EXPTIME.)

- Even a conservative estimate puts solving checkers at requiring more than 1,000 petabytes of storage space, which shows how large numbers can get with faster growing complexity classes.

Below are a few topics we felt like including so that one might do further research.

- What is a solved game?

- A solved game is a game where given a state of the game, assuming all players play perfectly, the result can be determined.

- A weakly solved game is when the above is true only given the starting state of the game, not any state.

- Thoughtful klondike is a solved game, whereas traditional klondike is not due to the cards being initially obscured from the player.

- Checkers can be considered the most complex weakly solved game to date.

- Why?

- High decision complexity: many moves to consider for each turn

- Moderate search space: many different possible game state

- Why?

Checkers-Specific Topics

- Forced Capture?

- Forced capture means that you must capture as many pieces as possible in your turn.

- This makes computation simpler because it forces players to rapidly remove pieces on the board, leading to a simpler game state.

- Contemporary Algorithm [10]

- Opening book of moves: compiled from grandmaster games

- Deep search algorithm: Looks for available moves, eliminating bad choices

- Move evaluation function: estimates a value of a move, instead of solving the value of the move

- End game database: All states of 8-10 pieces are stored in a database along with the best moves and outcome.

Finally, here are some additional resources that we crammed in here. Go forth and learn!

-

http://nature-of-computation.org/ ↩

-

https://core.ac.uk/reader/82132940 ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1906.12314.pdf ↩

-

https://www.ics.uci.edu/~eppstein/cgt/hard.html ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022000083900302?via%3Dihub ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0097316581900169?via%3Dihub ↩

-

https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2012/09/17/161096233/which-is-greater-the-number-of-sand-grains-on-earth-or-stars-in-the-sky ↩

-

Checkers Is Solved https://science.sciencemag.org/content/317/5844/1518 ↩

-

https://www.nextgov.com/emerging-tech/2019/06/massive-exabyte-storage-system-be-built-energys-frontier-supercomputer/157778/ ↩

-

Chinook https://webdocs.cs.ualberta.ca/~chinook/ ↩